Table of Contents

ToggleFood Packaging as an Operational System

Food packaging is often discussed as a visual or regulatory requirement, but in practice it operates as a complete system. It connects product protection, production speed, logistics efficiency, brand presentation, and compliance into a single physical object that must perform reliably under pressure. A package that looks correct on a design table can fail quickly once it enters high‑volume filling lines, mixed‑temperature storage, or multi‑stage distribution.

Modern food packaging decisions are therefore no longer isolated choices about material or shape. They are system‑level decisions influenced by how food is produced, handled, transported, displayed, and consumed. Businesses that understand this system avoid recurring damage, delays, and cost overruns. Those that do not often experience failures that appear random but are actually structural.

The Functional Roles of Food Packaging

Food packaging performs multiple roles simultaneously. When one role is over‑prioritised at the expense of others, performance suffers.

Product protection

is the primary function. Packaging must prevent contamination, moisture ingress, oxygen exposure, grease leakage, and physical damage. This role varies by product type. Dry foods require stability and barrier consistency, while fresh, frozen, or hot foods demand resistance to temperature shifts and condensation.

Operational efficiency

is equally critical. Packaging must move smoothly through filling lines, stacking systems, and distribution networks. Poorly designed packs slow assembly, increase waste, and create bottlenecks that raise labour costs.

Communication and branding

remain important, particularly in retail and takeaway environments. Packaging surfaces act as marketing space, but print quality must never compromise structural integrity or food safety.

Regulatory compliance

underpins every packaging decision. Materials, inks, adhesives, and coatings must meet food contact standards and regional legislation. Compliance failures create recall risk and long‑term brand damage.

Effective food packaging balances all four roles without relying on over‑engineering or unnecessary material use.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Food Packaging

Food packaging is best understood in layers, each solving different problems.

Primary Packaging

Primary packaging comes into direct contact with food. Its performance determines shelf life, safety, and consumer experience. Examples include cardboard food trays, pouches, wrappers, jars, paper cups, and bottles. Material selection focuses on barrier performance, chemical compatibility, heat tolerance, and sealing reliability.

Failures at this level are often subtle. Micro‑leaks, poor heat resistance, or weak seals may pass visual inspection but fail during transport or use.

Secondary Packaging

Secondary packaging groups primary units for handling, display, or portion control. Cartons, paper sleeves packaging, and trays fall into this category. Structural strength and dimensional accuracy are critical, as secondary packaging absorbs stacking loads and protects primary packs from compression.

Poor secondary design leads to crushed products, unstable displays, and inefficient shelf stocking.

Tertiary Packaging

Tertiary packaging protects food products during bulk transport and storage. Corrugated cartons, pallets, stretch wrap, and strapping systems are designed for compression resistance, load stability, and impact protection.

Mistakes at this level often involve using retail‑grade materials for transit environments, resulting in high damage rates despite compliant primary packaging.

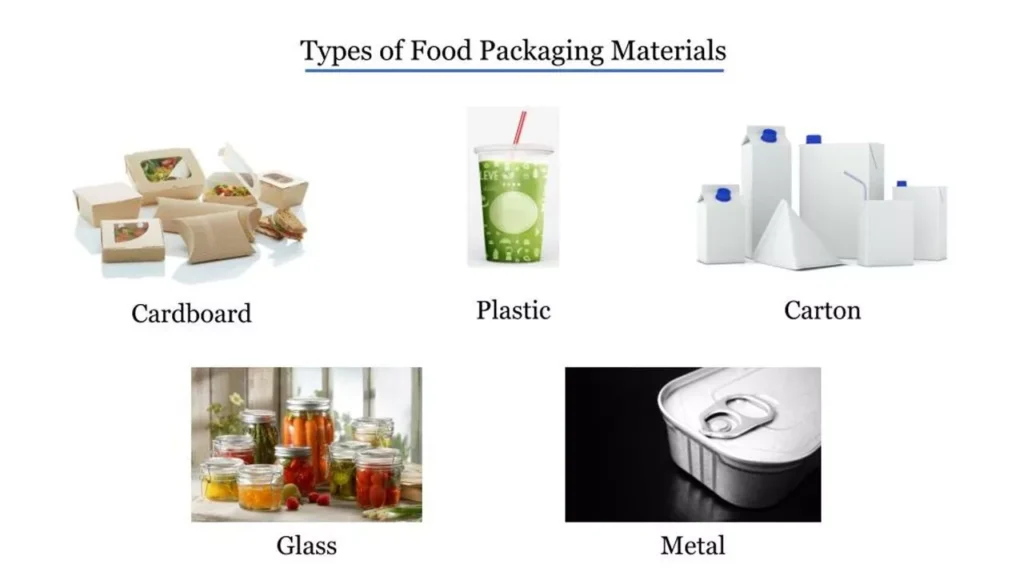

Food Packaging Materials and How They Behave

Material selection determines how packaging performs under temperature, humidity, handling stress, and time.

Paperboard and Fibre‑Based Materials

Paperboard is widely used for dry foods, takeaway items, and retail cartons. Performance depends on fibre quality, board thickness, and moisture resistance. Variations in fibre orientation and moisture content influence folding accuracy and compression strength.

Uncoated board offers recyclability and print clarity but performs poorly with grease or moisture. Coated and laminated boards improve resistance but introduce recycling trade‑offs.

Plastics

Plastics such as PET, PP, and PE offer excellent barrier control and heat resistance. They are common in ready‑meal trays, beverage containers, and flexible packaging. Performance is consistent, but sustainability concerns and regulatory pressure continue to reshape material choices.

Glass and Metal

Glass and metal provide superior barrier protection and long shelf life. Their drawbacks include weight, breakage risk, and higher transport costs. These materials are typically reserved for products requiring extended preservation.

Functional Films and Barriers

Barrier films, liners, and coatings are often layered onto base materials. These control oxygen transfer, moisture ingress, and grease migration. Performance depends on correct material pairing and application consistency.

Operational insight shows that barrier failures frequently originate from poor adhesion or uneven coating thickness rather than material choice itself.

Structural Design and Its Operational Impact

Structure determines how packaging handles stress throughout its lifecycle. Geometry influences load distribution, stacking behaviour, and assembly speed.

Flat‑pack designs dominate food packaging due to shipping efficiency. Their success depends on precise creasing, reinforced stress points, and predictable fold behaviour. Minor die‑cut inaccuracies can cause large‑scale failures when multiplied across thousands of units.

Pre‑assembled or rigid formats provide consistency but increase storage and transport costs. The correct choice depends on volume, automation level, and handling intensity.

Common Structural Stress Points

- Fold lines under repeated handling

- Corners exposed to stacking pressure

- Closures and locking tabs

- Base panels supporting product weight

Designs that distribute stress across multiple panels tolerate operational variation better than those relying on single load paths.

Quality Control Beyond Visual Inspection

Quality control in food packaging often focuses on appearance, weight, and basic dimensions. These checks are necessary but insufficient.

Critical but frequently missed QC checkpoints include fold depth consistency, glue bond strength at line speed, dimensional drift across long runs, and performance under temperature and humidity variation. Packaging that passes initial inspection may still fail after repeated folding cycles or exposure to condensation. These failures emerge during peak demand when tolerance margins are already strained.

Effective QC combines lab testing with real‑world assembly trials and stress simulation.

Failure Scenarios in Food Packaging Operations

Most packaging failures are cumulative rather than sudden. Slightly weakened materials, rushed assembly, and uneven stacking combine to produce visible defects.

Typical failure outcomes include split seams, bowed panels, crushed corners, leaking grease, and unstable stacks. These issues disrupt workflows, damage products, and increase returns. Design mitigation strategies focus on controlled flexibility, reinforced load paths, tolerant closures, and predictable assembly behaviour. Robust packaging does not require perfection in handling to perform reliably.

Comparing Packaging Structures

| Performance Factor | Flat‑Pack Structures | Rigid or Pre‑Assembled Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Storage efficiency | High | Low |

| Transport cost | Lower | Higher |

| Assembly variability | Moderate | Low |

| Structural consistency | Dependent on folds | Highly consistent |

| Typical failures | Misfolding, corner stress | Surface damage, crushing |

The correct structure depends on operational realities rather than visual preference.

Packaging Use Cases and Material Performance

| Use Scenario | Key Material Properties | Operational Outcome |

| Hot food | Heat resistance, grease control | Maintains shape and safety |

| Cold or chilled food | Moisture resistance | Prevents softening and leaks |

| Retail display | Surface smoothness, rigidity | Shelf stability and print clarity |

| Transit and distribution | Compression strength | Reduced damage rates |

Selecting materials without considering end‑to‑end use conditions is a common source of failure.

Sustainability Without Functional Loss

Sustainable food packaging must balance environmental goals with performance requirements. Over‑lightweighting reduces material use but narrows tolerance margins. Over‑engineering wastes resources and increases cost.

Effective sustainability strategies include material optimisation, mono‑material designs, reduced coatings, and improved shipping efficiency. Sustainability should improve system performance, not undermine it.

Commercial and Cost Considerations

Food packaging costs reflect raw material volatility, energy prices, tooling investment, labour, and compliance testing. Commercial models vary from long‑term supply contracts to co‑packing and private‑label production.

Early engagement with packaging partners reduces redesign cycles and prevents costly late‑stage changes.

Practical Steps for Food Businesses

- Define performance targets based on product behaviour

- Map distribution and handling conditions

- Screen materials against barrier, cost, and machine compatibility

- Prototype under real operational conditions

- Budget for testing and pilot runs

Final Perspective

Modern food packaging is not a static container but a working component of food operations. When materials, structure, quality control, and operational realities align, packaging becomes a stabilising force rather than a recurring problem. Businesses that treat packaging as a system gain reliability, efficiency, and long‑term cost control, turning packaging from a hidden risk into a strategic asset.